As road owners around the world look for lower-carbon and longer-lasting roads, the list of ingredients that go into a mix design gets ever longer. It could include recycled asphalt pavement (RAP), crumb rubber, warm-mix additives, rejuvenators or polymer modified bitumen (PMB), to name but a few.

Yet, in many markets, the testing regime remains unchanged. “Traditional testing is very popular, but it only allows a ranking of the mix,” explained Andrea Carlessi, product manager at testing equipment specialist CONTROLS. “The big limitation is that it does not allow you to understand the behaviour of the mix, it cannot detect the properties that come from adding these new materials.”

An alternative approach is performance testing. Rather than check that the various elements of a mix meet set criteria and then combining them in specified volumetric proportions, performance testing aims to look at how the mix will actually perform on a particular road.

The idea of performance testing is not new. It is used extensively in the US, Canada, China and to some extent in France, UK, Netherlands, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Russia. However, Carlessi believes that performance testing is entering a new phase of development.

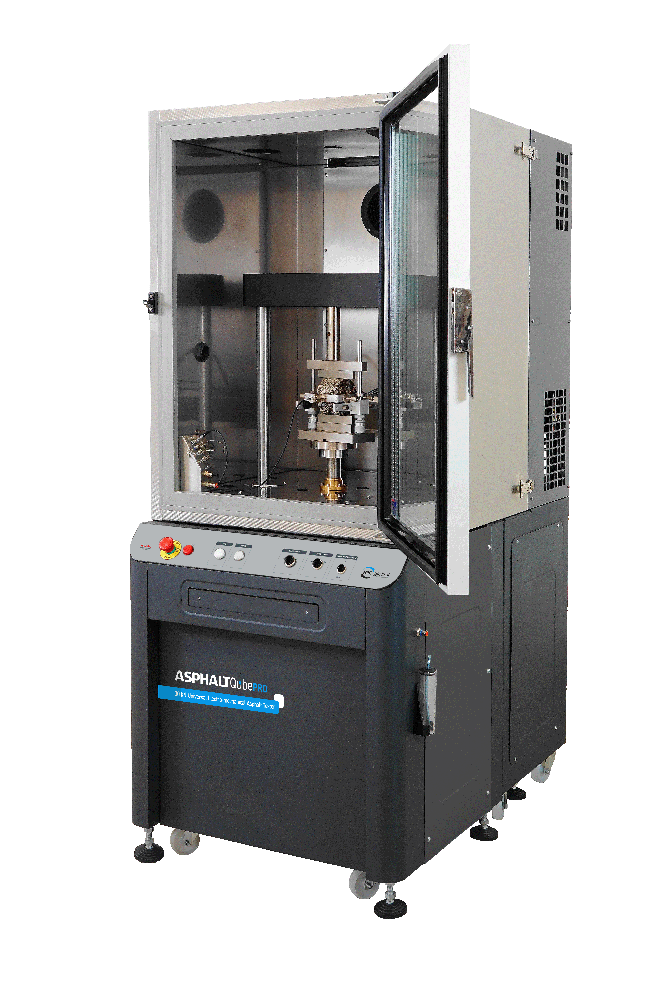

“New technology goes in cycles. Currently we are in a phase with performance testing where we are looking for simplification,” he said. “This applies to both specifications and testing equipment.” Recent equipment launches from CONTROLS which demonstrate this theme include the Balanced Loader which can automatically perform a range of bench compressions tests and the AsphaltQube Pro, which is a research-oriented version of electro-mechanical AsphaltQube.

The US’s Balanced Mix Design approach shows how the specification simplification process could work, says Carlessi. Balanced Mix Design involves balancing out the rutting and cracking performance of a mix so that it meets the required traffic loading, location and environment. This is done by carrying out a series of tests on appropriately prepared specimens.

Although the term ‘Balanced Mix Design’ was coined by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) back in 2015, the first standards relating to this approach have only recently been published by the American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO). AASHTO PP 105-20 Standard Practice for Balanced Design of Asphalt Mixtures sets out routes for four different approaches to balanced mix design. AASHTO MP 46 Standard Specification for Balanced Mix Design specifies minimum performance testing requirements for balanced design of asphalt mixtures. Both were published in July 2020.

One of the challenges for any road authority looking to adopt Balanced Mix Design is that there are multiple tests which can be used to test the various types of pavement distress, according to Carlessi. For instance, rutting could be tested using a Hamburg Wheel Test and Asphalt Pavement Analyser, an Indirect Tensile Tests(IDT) – at high temperature (HT) or an AMPT (Asphalt Mixture Performance Tester) for flow number and dynamic modulus.

“With traditional testing, such as the Marshall Test, everybody in the world was doing the same thing, they were using the same language,” said Carlessi. “With performance testing, there is a more confused situation.” Practice varies from country to country and – within the US – from state to state.

Another downside of this disparate approach to testing is that it can limit innovation, said Carlessi: “Because there is a huge dispersion of the market in terms of the variety of testing equipment needed in different markets, it is very difficult to focus on a small number of machines in order to carry out next-level innovation.”

However, Carlessi predicts that the range of tests will reduce, as performance testing becomes more widespread and the most effective tests are identified. “My hope as a manufacturer is that, over time, we will have more defined tests which will then help push our knowledge, technology and the market further ahead,” he said. “Balanced Mix Design is a very good first step in the right direction.”

AI could revolutionise mix design

In May 2022, Ottawa tech firm Giatec Scientific and global cement producer HeidelbergCement announced a deal aimed to speed up the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) to design concrete mix designs. With the plethora of materials sources, temperatures, curing conditions and other variables that go into a finished concrete road or structure, the hope is that AI can learn from Heidelberg’s huge volumes of historic data to optimise designs in terms of quality, capital cost and – crucially – carbon.

The deal sees Heidelberg taking a small share in Giatec, which specialises in wireless sensors which are used to predict the curing time of concrete by measuring its heat. The amount of Heidleberg’s investment has not been revealed, but for the tech firm, the important part of the deal is the access to Heidleberg’s data which comes from operations in over 1,500 plants in 50 different countries.

“When we were building the algorithm, one thing we learned was that the location of the data makes a big impact on how good the algorithms are,” said Andrew Fahim, Giatec’s research and development director. Heidleberg’s involvement means that it should be possible to create algorithms that work in multiple countries.

“We need to get these technologies out to the people who are pouring the most concrete,” said Fahim. “although we have had a lot of interest from European partners, as well as those in North America, a lot of concrete is being poured in developing countries.”

Giatec started developing its web-based mix design tool, SmartMix, around three years ago when it realised that it had collected data from around 5,000 projects. Two years ago it started working with a group of 20 cement producers, mostly from North America, using their data to further enhance and train the algorithms.

Around a year ago, Giatec started working on pilots with five of the producers and at the same time released SmartMix publicly. Discussions with Heidleberg followed.

One of the challenges in accessing the data to train the SmartMix algorithms is transferring it from the Batch and Dispatch systems used at concrete plants, explains Fahim. SmartMix can already hook up with Marcotte Systems software, with Giatec aiming to provide the same ability for the other main systems used around the world in around two years’ time. In the meantime, it has built and released an open API (application programming interface) which allows SmartMix to ‘talk’ to other software.

There are hurdles to clear – not least the use of prescriptive standards – before SmartMix can be more widely used but Giatec predicts multiple benefits in the future. As well as reducing the carbon footprint of concrete, perhaps by substituting Portland Cement with fly ash or slag, Giatec hopes SmartMix’s algorithms should help to avoid failures and increase concrete quality.