It’s the middle of the night and in the street below a team is busy carrying out repairs to the road surface. But there isn’t a human in sight.

A road-repair drone has landed at the site of a crack and a 3D asphalt printer is now busy filling in that crack. A group of traffic cone drones have positioned themselves around the repair location to protect the repair drone and divert traffic around it.

This scenario may not be as futuristic as it seems. Researchers from Leeds University have already created a prototype of such a drone, while colleagues from University College London have managed to build the world’s first bitumen 3D printer. Both the drone and printer projects are part of a wider research programme called Self Repairing Cities.

“Our 2050 vision is to have zero-disruption road works,” says Richard Jackson, a research associate at UCL who developed the 3D bitumen printer. “It will be quieter, so we can do it at night and the goal is to have no human input at all.”

The 3D bitumen printer has already attracted the attention of several major road contractors. They are interested in a shorter-term solution using a semi-automated process, rather than a full-blown drone-delivered repair, says Jackson.

Jackson’s project has also produced another surprising result relating to the material properties of the printed bitumen. The process of extruding the bitumen through the nozzle of the printer seems to have changed the properties of the bitumen, when compared to the properties of exactly the same material which has just been heated up and cast.

Preventative maintenance

The concept of the road-repair drone with its 3D printer is based on the idea of preventative maintenance. Road surfaces could be continually scanned – for example, using devices attached to the underside of municipal vehicles such as refuse wagons – and any small cracks treated soon after identification.

Filling cracks early would prevent them worsening and hence extend the life of the road surface. Using drones, rather than crews of human repairers would make such a regime much more affordable, notes Jackson. “The cost would be so much less.”

“As scientists, we like to ask questions like ‘could we put a flame thrower on a drone?’,” says Jackson. “And after the asphalt has been printed, are we going to compact it, or will each function be carried out by a different drone?”

The 3D printer Jackson designed is a three-axis system with individual stepper motors that move the printed nozzle around. A six-axis system might be more useful, although it would also be a lot heavier.

The nozzle itself is made up of an auger screw, a stepper motor to drive the screw and a pellet hopper which fees in bitumen pellets. Heating resistors warm up the pellets and turn them from solid to liquid as they pass through the auger and out through a 2mm aperture.

Over the two-and-a-half years that he has worked on the project, Jackson has tried various iterations of nozzle and auger screw design before finding the optimum combination. He also experimented with different temperatures and screw speeds, settling on between 125°C and 135°C at 1mm/second print speed and 4.4 rpm.

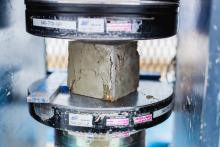

Before using it to fill cracks – which the drone has done in a Leeds University car park – Jackson used the printer to create bars of bitumen for testing. In comparing the performance of these bars to cast ones, the unexpected difference in mechanical properties was revealed.

The cast bar showed different performance depending on which way up it was tested, whereas the printed one didn’t. The printed bar also showed up to nine times the ductility of the cast one, with similar fracture strengths.

The possible cause of the difference was revealed by closer observation of the form of the bitumen. The printed sample was found to contain a stretchy brown substance dotted throughout its cross-section which wasn’t seen in the cast one.

Jackson hypothesises that the brown, crack-bridging substance that seems to increase ductility is composed of a lighter saturated faction of the asphalt that has formed due to the way various sizes of particle move during the heating, screwing and extrusion process. “I have done some other work involving nano-fibres and the printing process influences the fibres quite strangely too.”

Concrete, too

Though not part of the Self Repairing Cities project, researchers at Texas A& M University have also been experimenting with 3D printing to repair spall damage in concrete roads. This often occurs around induced cracks in concrete road surfaces, where lumps of concrete break off.

The researchers used photogrammetry software, Autodesk ReMake, to create a computer model of the spall damage, which they then had to adjust to make sure it was the right size. This model was used to create a plastic formwork into which concrete was poured.

The concrete patch was then glued into the hole using an epoxy-resin adhesive. This also served to take up the gap created by shrinkage of the concrete, says Yeon.

To date, this technique has been used for two holes in the university’s car park. It will be important to prove the longevity of the technique before moving to trials on heavily-trafficked road due to the potential risks to motorists if the patching fails, says Yeon.

The researchers also calculated what the economic benefits could be of this faster repair method, using the

Next steps

At UCL, Jackson is now working on printing asphalt mixes, rather than just the bitumen binder. Adding aggregates is problematic at the moment at this small scale, says Jackson, although a combination of sand and bitumen can be printed.

3D printing would allow the material to be varied over the depth of the crack, switching feedstock to apply a different material for the upper surface for example. Jackson is also adding nanomaterials, such as titanium dioxide nano particles.

This method will allow for printed materials to be tailored according to the location of the road and the local specifications. The nozzle and its operating parameters could be adjusted accordingly. “There is an argument for machine learning in the design,” he says. “We need a factory to make the 3D printing robots with different properties depending on the materials used in the road.”

Even in the shorter term, without total automation, 3D printing crack repairs could save money, says Jackson. And this is why contractors are interested in the technology.

A logistics app could organise and direct a small repair crew to crack locations, perhaps in an automated vehicle, optimising the work schedule, routes and timings. The crew would bring a ‘black box’ which would use computer vision technology to position its 3D printer over the crack and fill it accordingly.

“3D printing is going to change a lot of fields,” says Jackson who worked in nanotechnology and medical devices before he moved to this project, “and it definitely has the potential to change this one.”