Apps for personal use can take only days to deliver. However, this is in stark contrast with how long it can take to set up IT solutions in the public sector. Requests for proposals alone typically extend into months and delivery sometimes into years. Also, within the public sector, risk in terms of money, reputation and public support encourages a play-it-safe attitude. Yet, as many leisure and comfort-oriented apps show, far more can be achieved if concerns over failure are removed or substantially reduced. This is precisely what Esri, a global information services company, has set out to address with its own System of Engagement (SoE), an app-centric approach to connecting people, processes and data (see box).

The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DoTD) is using Esri’s SoE to fast-track development of apps which are transforming its operations. Through a combination of its own commercial-off-the shelf products and close engagement with clients, Esri’s SoE dramatically reduces the time for organisations to conceptualise, develop and implement apps. The commercial off-the-shelf approach does away with bespoke products. In many cases it reduces from months to weeks the time taken to get an app into the hands of users. Only a year on from giving Esri’s SoE the green light, the DoTD has fielded over 30 new apps.

Quick start

The DoTD had been searching for a way to tie together its disparate business systems for more than two decades, according to Brad Doucet, director of enterprise support services. “The problem was that we’re a large and mature organisation that creates and owns a lot of data. To use analytics, to meet the needs of federal reporting as well as to partners and internally, we had to have a more efficient system of accessing and exposing the data,” he explains.

“We decided to keep our systems of records in place and use the System of Engagement to tap into and develop apps to address specific problems. There are a lot of moving parts,” he continues. “Our IT department split off and was centralised in the state government’s Office of Technology Services about five years ago. It came to a point where we had three major parties that had to be in lock-step with each other for this all to happen. That collaboration, especially in year one between Esri, DoTD and Office of Technology. That’s been our greatest success.”

DoTD looked at several solutions but Doucet notes that these were “essentially data warehouses or lakes which put all data in one place but then leave you searching for a way to tie information together.” Recognising that the one thing all data has is location and that DoTD wanted to present information in a geospatial format made Esri’s GIS-based SoE the natural choice, he says.

The SoE starts with a series of Business and Discovery Workshops, with Esri onsite. These scope what the client is looking to achieve and what technology and data will be needed.

By the end of that process, DoTD had identified 61 apps that would help drive their performance and create greater efficiencies. Prioritisation reduced that to 15, recognising that in year one creating the technical foundation for future work would also be happening. The first year was like “building the aircraft while flying it”, according to Doucet.

“Once we started to look at those 15 apps and the technical work needed, the number turned into a little over 30. This was based on the technical tools available to us and the most efficient way to do things. It’s an interactive effort. We’re using Agile project-management techniques. If we fail, we’ll do so quickly and small. We don’t have to wait a year to see that something doesn’t work. It’s that iterative process which enables all this to happen,” he says.

Agile project-management techniques were a revelation for some people within DoTD, notes Doucet. “Typically in IT, you put all of your systems requirements together and talk to your business leaders up front. Your technical people then go off and build something for you and maybe come back three to six months later. In today’s climate, business needs could have changed in that amount of time and any miscommunication up-front can cause real issues. Instead, we had weekly progress meetings.”

App development

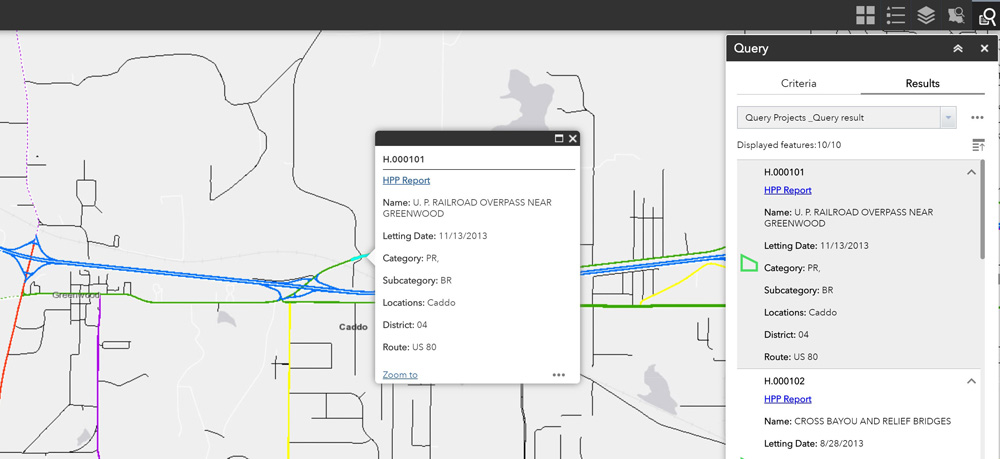

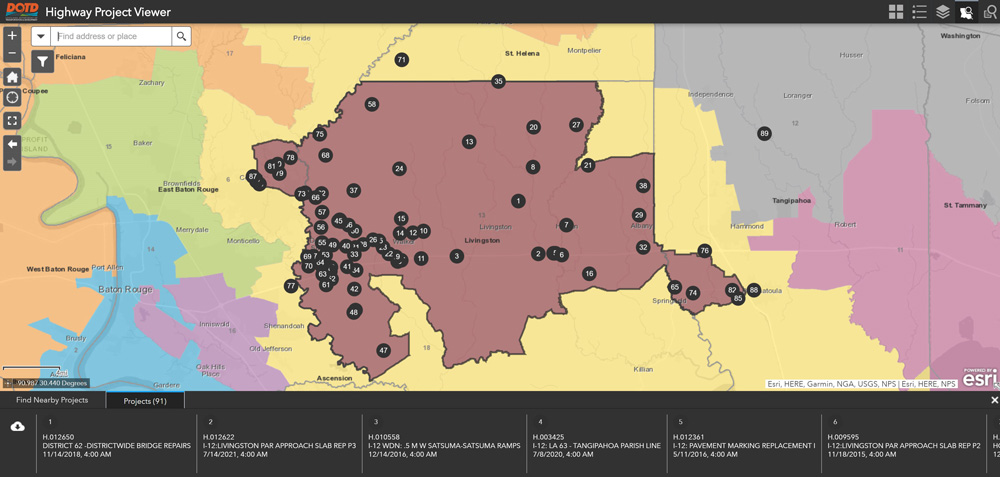

One of DoTD’s most widely used apps, the Highway Projects Viewer, which gives information on construction projects, illustrates how the SoE works. Using a suite of commercial off-the-shelf tools, Esri was able to bring together information from multiple sources and package it in one place.

“It’s not a custom development. That’s something we really wanted to stay away from. But it’s easily developable without us needing to have a specialist on board at all times,” says Doucet. “Just about every DoTD employee can access it. They can go to one place and get to the information they need, rather than three or four places as before, if indeed they even had access to all of those other systems.”

Universal access and its speed are key differentiators. For example, DoTD has also created a 511 Road Closures app that is far more user-friendly than the state’s existing 511 app. The new app very easily picks points in time, and locations, and users then can see closures.

Field operatives have also benefited considerably. For example, the Soil Band App has replaced environmental engineers’ hand-written notes. “Previously, that information in notebooks was taken back to an office and we used a desktop graphics editor to create an image of what we had. Now, we have forms on a tablet or phone and the relevant graphs are automatically generated,” says Doucet.

“It’s been estimated that the suite of field apps that we’ve developed for our environmental engineers saves 300 man-hours per project. That was a small, readily configurable suite of apps that we created through the System of Engagement that has resulted in a tremendous positive impact to DoTD.”

Exposing data to more scrutiny and comment creates a virtuous cycle of quality improvement, says Doucet. “That’s been one of the chief benefits. Before, because everything was siloed, only a limited number of folks could see the data and know whether it was right or not. Now, because more folks see it, it’s accuracy can be challenged and any incorrect data can be remedied.”

Doucet notes that there has been “overwhelmingly good” feedback from the people who use these apps. “A challenge in the first year, given our finite resources, has been keeping up with those who want to be a part of this. Even where apps have already been developed, people are wanting to add to them because they see how they make their jobs easier. “That’s going to allow us to get more governance," he says.

An example of this is the Highways Project Viewer where construction is the last phase. “There are five other phases that we have data for that’s not on the Viewer at present. Some other ideas for apps may not fit into existing apps. We may even reach a point of retiring some apps, although I don’t see that happening at this stage,” he says.

Real value

“It’s clear, though, that the tools we’ve created allow us to do things of real value. For example, we’re a very flat state with a long coastline and an app we’re looking to develop in year two is for flood inundation. This is a predictive tool, based on elevation. If a surge comes up from a hurricane and we have ‘X’ many inches of rain, which roads can we expect to flood? We have LiDAR data and we’re collecting enhanced data to work out where those roads would be and then work through our Emergency Management Center to manage that.”

With the technical foundations in place, Doucet says that year two and onwards will see accelerated expansion and improvement of the app set. “How all this is constructed and configured through commercial off-the-shelf products encourages joint working, as compared to simply getting a contractor in to build a system that then has to be somehow maintained,” says Doucet.

“A good thing about the System of Engagement is its sustainability over time. It’s a different approach to IT, replacing those big, custom one-offs with something much easier to implement and work with.”

Systems of Engagement

Systems of engagement are decentralised IT components that use technologies such as social media and the cloud to encourage and enable peer interaction. A system of engagement differs from a system of record which is an information storage and retrieval system. A system of record provides a centralised, authoritative source of data elements in an IT environment containing multiple points of data generation.

Moving away from systems of record and toward systems of engagement requires major changes to content management processes and strategies. Disconnected systems such as supply chains, vendor ecosystems and business operations must be integrated to operate as a unified whole under systems of engagement. To achieve this integration, cloud-based platform technologies are often deployed to enhance collaboration. These changes to content management systems also likely require new processes for securing, storing and deleting records.