London’s recent two-day MOVE exhibition on urban mobility featured everything from electric cars and delivery vans to scooters, family tricycles cycle-hire operators and ride hail on-demand companies.There were dozens of start-up companies offering a myriad of fleet management solutions, drone delivery, traffic data management platforms and electric vehicle charging systems.

The exhibition hall was alive with the youthful enthusiasm of young employees who believe that they and their products can make a real improvement in urban mobility. They can help make cities more liveable, with cleaner air and more green spaces. And do this while having fun getting around in.

Also exhibiting was Volvo Construction Equipment. The company had a zero tail-swing electric excavator ECR25 on their stand. Meanwhile, its latest all-electric wheeled loader L25 was in the demonstration area, trundling around among electric scooters, delivery and rental bicycles and autonomous urban tricycles.

But what on earth is a global construction equipment manufacturer doing at an urban mobility solutions exhibition? Excavator operators don’t drive home in their machines and use them for pleasure for the weekend.

While that may be so, they, the electric machine manufacturer and the contractor using the machines are part of what Mats Bredborg at Volvo CE calls the net-zero carbon reduction value chain. Better urban mobility is essentially about creating a better living environment. Electric construction machinery is part of creating that better environment.

Many cities around the world are moving towards low emission zones that limit the use of fossil-fuel vehicles, either totally or periodically. Many, such as London, are expanding their zone further from the city centre outwards to suburbs.

This strategy is part of the increasing trend to multimodal transportation geared towards providing a more liveable city including cleaner air. In this respect, how cities approach this will directly affect the construction equipment manufacturer, explained Bredborg, who is Volvo CE’s head of “customer cluster utility”, during his 20-minute presentation in one of the session rooms.

Electric machines, especially the small excavators and loaders, are increasingly popular with city authorities which are trying to maintain a quieter and also a cleaner environment. Specifying their use in urban areas is becoming more common. However, it is one thing to specify their use, says Bredborg. There needs to be a vision of the more complex, interconnected - and often subtle – net-zero value chain.

“These low emission zones have led to a surge in sales for [electric] taxis, buses and cars. Now you have to create larger charging infrastructure. We are pushing very hard to be allowed to use this infrastructure for our electric machines. It also doesn’t make any sense to have diesel machines building charging stations. There has already been a lot of investment in these charging stations and Shell is going to build 100,000 charge points in the UK over the next two years.

Shell also has transformed a traditional petrol filling station in London into a fast-charge electric-only station - no more petrol pumps. Bredborg says that Volvo is hoping to use their electric machines to build some of these stations - and be able to use their electricity in the process. “This is a good example of partnering in this value chain,” he says.

“When you look at electric charging, you have to think end to end, the entire net-zero value change. It is no good having a Volvo customer buy an electric machine and then they cannot use it because onsite there is no access to electricity. This being the case, at the end of the shift the machine would be loaded up an taken back to the contractor’s yard to be recharged. This pick up and return actually creates CO2 transport vehicle emissions.”

It would be better, he says, if electricity was made available onsite. Or there were deals where these small machines could be recharged at a regular vehicle charging station, overnight, for example. Or that such facilities were made available at recharging station forecourts. This cuts down on CO2-producing transportation.

The interesting thing is that in cities we have found that we are never more than 20m away from electricity, but it’s not our electricity! So you need a value-chain partnership to get access to that electricity. “Smaller machines recharging are not going to collapse a city’s electricity grid, either.”

Similar to many companies in all sectors, not only manufacturing, Volvo CE has embraced the net-zero philosophy for their own production. The plan is to be a net-zero manufacturer within 30 years, by 2050. To achieve this, it must have completely phased out its diesel-powered units operating on sites. But a machine has around a 10-year lifespan, meaning Volvo CE must not be selling diesel units at least a decade before 2050.

“So, by 2040, all Volvo construction equipment machines being sold will not operate on fossil fuel,” says Bredborg.

That is only 18 years from now; the pressure is on. “We have a portfolio of about 200 different products out there [operating on sites] but only five are fully electric and there is another five not yet commercially available.”

Non-fossil fuels

Different types of non-fossil fuel technologies will be used because not one size fits all – different fuels will be for different construction efforts and worksite situations. Battery electric, which is available now, is the first. Volvo CE will launch a 600-volt system for machines in the near future.

Volvo CE is working on fuel cell electric development as the next step along its path to net-zero. They have technology partners as well as agreements with Daimler Benz. “But this is a technology that is further out from the present.”

The smaller machines don’t require that much energy, so they can remain as battery-only units. “Think of construction machines on sites in cities. They may work a few hours only, not all day. But the bigger machines may have to work three shifts a day, seven days a week. So they need more power. For this reason it is looking like these larger units will have to be hydrogen-powered.

There are some mid-range machines that are deployed in stationary positions for some time and these could be powered by battery units, either large standalone battery stations on site that can deliver power to a large machine working nearby. Or, if enough power is available, the large machine could be hooked up to the grid while working onsite.

Even though the battery technology is commercially available, it is still being refined and upgraded with better power output and faster charging. “This challenge we can’t take on ourselves but need many different partners. It is also about making machines more efficient to operate.”

If they use less power for the same amount of work, the operating carbon footprint goes down. This efficiency is up to how the machine is used to conserve battery energy.

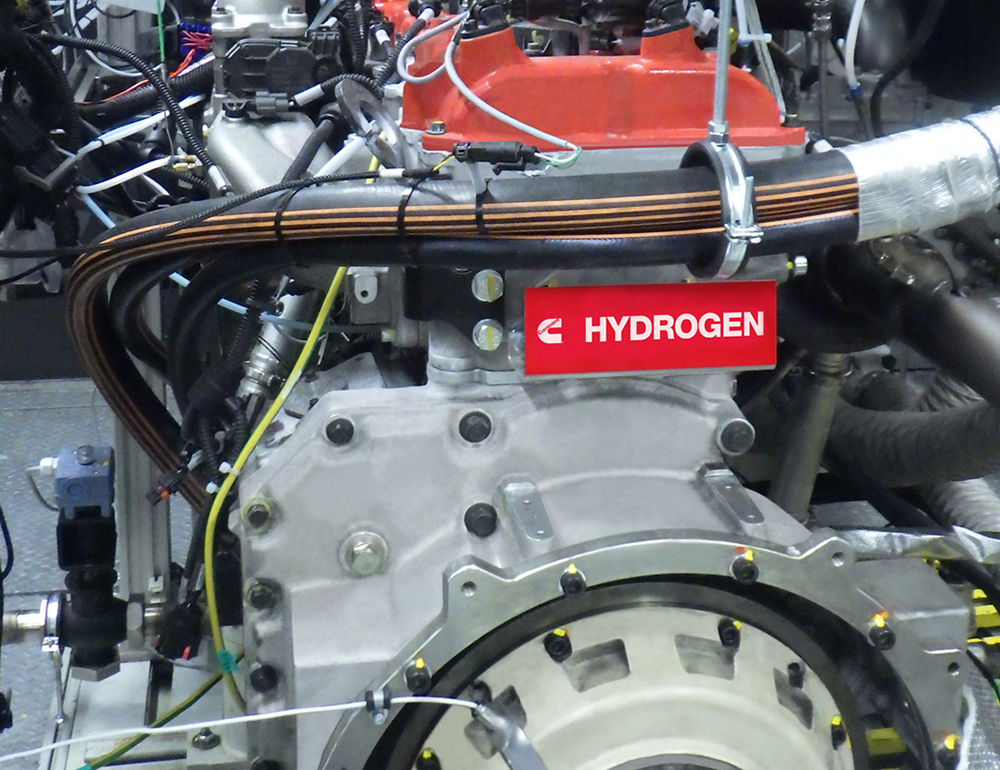

Volvo CE started its hydrogen-powered development in 2018 and only in June did the company roll out the first prototype for testing, an articulated hauler. “It has a 25tonne payload, quite heavy, and we can fuel it in under 10 minutes with hydrogen and that will last about four hours of operation. But we still have loads of challenges in this area. Not sure if we have even made it work for a full day yet. The technology really is in the early stages.”

Fossil-free steel

Construction machines are typically 80 per cent steel and production of steel comes with a very large carbon footprint, he says. Production of that one tonne of steel in turn produces 1.8tonnes of CO2. “We are working with the steel firm SSAB to manufacture the first vehicle in the world using only fossil-free steel. The interesting thing about producing fossil-free steel is that one of the by-products is hydrogen,” her says (see box, Fossil-free).

“Another issue using hydrogen technology is that we don’t have the technology to carry 150tonnes. We have the technology to carry only 10 to 15 tonnes. Instead of having one 150tonne truck, we have 10 15tonne trucks. But if you now have 10 trucks, you will need 10 drivers, and that becomes a big cost.”

However, if you make the trucks autonomous, one operator can drive them in a series. “We go from making bigger and bigger products to making smaller and smaller products.” He says they could be like “like ants” where they work together for the bigger result.

While technology for charging bigger machines faster is coming along, there has to be innovation around how and when a machine is charged. A contractor could truck onto site a stationary battery recharging system that has been charged offsite. Once unloaded onsite, an excavator could hook up at the end of the shift or during a lunch break.

While technology for charging bigger machines faster is coming along, there has to be innovation around how and when a machine is charged. A contractor could truck onto site a stationary battery recharging system that has been charged offsite. Once unloaded onsite, an excavator could hook up at the end of the shift or during a lunch break.

However, if the large machine is not near the stationary recharging system, a smaller portable battery recharging unit could be charged from the stationary system and taken to the machine needing to be recharged. This is another example of scaling the technology to suit the situation, says Bredborg. Volvo CE is already working on these type of onsite charging systems and has a prototype operation underway in Norway right now.

For small machines working in urban environments, there is usually some access to electricity. Onsite construction teams could have small portable fast-chargers that can be connected to a supply onsite or delivered to a site if no connection is available.

These portable units could then fast-charge a machine during lunchtime or slow-charge them overnight. But as Bredborg notes, these smaller machines even now can usually work four to eight hours anyway; charging them overnight is likely the easiest and best option. This idea is popular in Europe, he says, where the company launched its small electric machines in 12 countries in 2020. This year Volvo CE recently launched their small electric units into the North American market.

Speaking to World Highways, Bredborg emphasised that the electric machine manufacturers are tied into the entire net-zero value chain.

“A construction company likely wouldn’t simply go and buy an electric machine. The demand for electric machines starts with the local government, cities and municipalities saying they are going zero-emission. So it then goes down to the engineering and construction companies buying required electric machines and on it goes down the value chain. In this way we are not selling construction equipment but offering rather CO2 reduction.”

“National Highways are building charging stations outside cities and they have a target for carbon reduction,” says Bredborg. “We then sell that solution to help them meet that target.”

Green for hydrogen:

Volvo CE announced in June that it has started testing what it says is the world’s first fuel cell articulated hauler prototype, the HX04, where the results will provide insight into the possibilities provided by hydrogen and fuel cells. The fueling process for hydrogen vehicles is fast – the Volvo HX04 is charged with 12kg of hydrogen in around 7.5 minutes, enabling it to operate for about four hours. Fuel cells work by combining hydrogen with oxygen and the resulting chemical reaction produces electricity which powers the machine. In the process, fuel cells also produce heat that can be used for heating the cab. Hydrogen fuel cells emit only one thing – water vapour (image courtesy Volvo CE).

Fossil-free, the A30G

On June 1, a single A30G articulated hauler, built using fossil-free steel, was handed over to NCC, a major Nordic construction company based near Stockholm, Sweden, and a long-standing Volvo CE customer. The hand over was done by Melker Jernberg, president of Volvo CE.

The ceremony itself was hosted by LeadIt – the Leadership Group for Industry Transition. LeadIt gathers countries and companies that are committed to achieving the Paris Agreement on climate change. It was launched by the governments of Sweden and India at the UN Climate Action Summit in September 2019 and is supported by the World Economic Forum.

The handing over ceremony for the A30G was done within the United Nations environmental meeting called Stockholm +50. The meeting was an international event convened by the UN General Assembly to commemorate the 50 years since the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment, which made the environment a pressing global issue.

Volvo CE said that the handing over comes only nine months after the company unveiled the world’s first vehicle concept using fossil-free steel, as part of the testing of the implementation in an ordinary production setup. While commercial introduction is expected to be gradual with selected customers, Volvo group noted that this speedy first handover is an important milestone in the group’s ambition to drive industry transformation towards global climate goals.

The A30G weighs 23,300kg and has a payload of 29,000kg. It is produced at Volvo CE’s Braås facility in Sweden using an existing manufacturing process and with fossil-free steel from Swedish steel company SSAB.