Work zones are a well-recognised potential hazard on our roads. They can be dangerous both for road users who have to manoeuvre through less than ideal road conditions, but also for those workers who build, repair, and maintain our roads, bridges, and highways. For this latter group, a road construction zone also represents their work environment.

It is difficult to obtain international injury and fatality statistics for work zones, and this in itself could be an indicator that the issue is not being addressed with the appropriate level of priority. What we do know is that in 2015, the US Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) reported over 25,000 work zone crashes that involved at least one injured party of which 642 resulted in at least one fatality. These figures suggest that, taken at global level, hundreds of thousands of injuries and thousands of fatalities occur every year in work zones.

Work zones represent a particularly serious safety concern in the developing world, where an abundance of road rehabilitation projects have, by and large, not been accompanied by commensurate investments to foster a safety culture on road construction sites.

Earlier this year, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) published a set of work zone safety guidelines applying to the Trans-European Motorways. The report notes that a growing number of countries have adopted road safety strategies based on the Safe System approach, which takes as its starting point the position that there is no acceptable level of road deaths or serious injuries. However, road work zones are rarely governed by the same philosophy.

Similar to the rest of the road network, work zones need to be designed and managed so that the potential for injury is eliminated or significantly reduced. The report concludes “All processes associated with roadworks must be undertaken using Safe System principles…. Construction workers and road users are all put in danger whenever risks are not adequately assessed and addressed”.

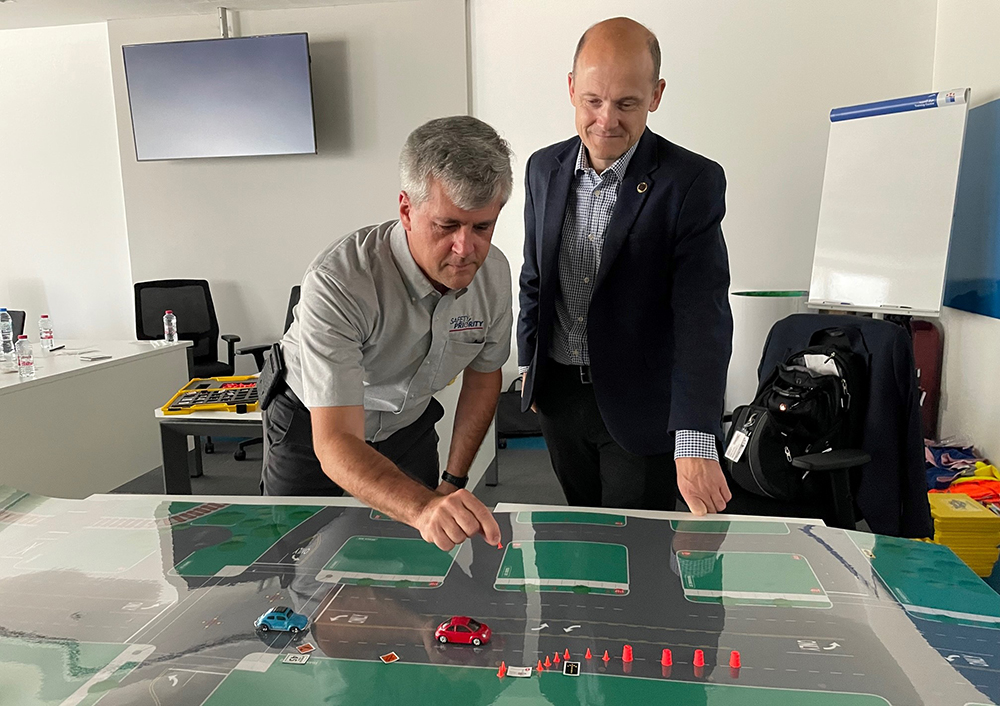

Opening a recent training event in Dubai (pictured above), lead IRF instructor Chip Darius noted that “Improvised and inconsistent work zones cause confusion, reduce reaction time, and increase risk. Consistency is key to safer work zones. Standards are the key to consistency. Training gives knowledge of the standards. The system works best when trained workers adhere to standards for safer work zones.”

Building on this report as well as other available resources and industry know-how, IRF has scaled up its recent advocacy and capacity-building initiatives to ensure more government agencies have access to state-of-the-art processes and technologies.