Political hostility to a toll road project in Australia has been turned around by the quality and amenity of the project writes Adrian Greeman Cars, trucks and vans were taking to the new EastLink toll road in Melbourne with enthusiasm this July, pleased to try out its 39km route for time and cost savings. As well as the convenience of the uncongested route, drivers were also able to view an extraordinary multi-shaded perspective of transparent green and orange noise wall panels, burnt earth-coloured retai

The design of the project has been augmented by environmental features and artworks

Political hostility to a toll road project in Australia has been turned around by the quality and amenity of the project writes Adrian Greeman

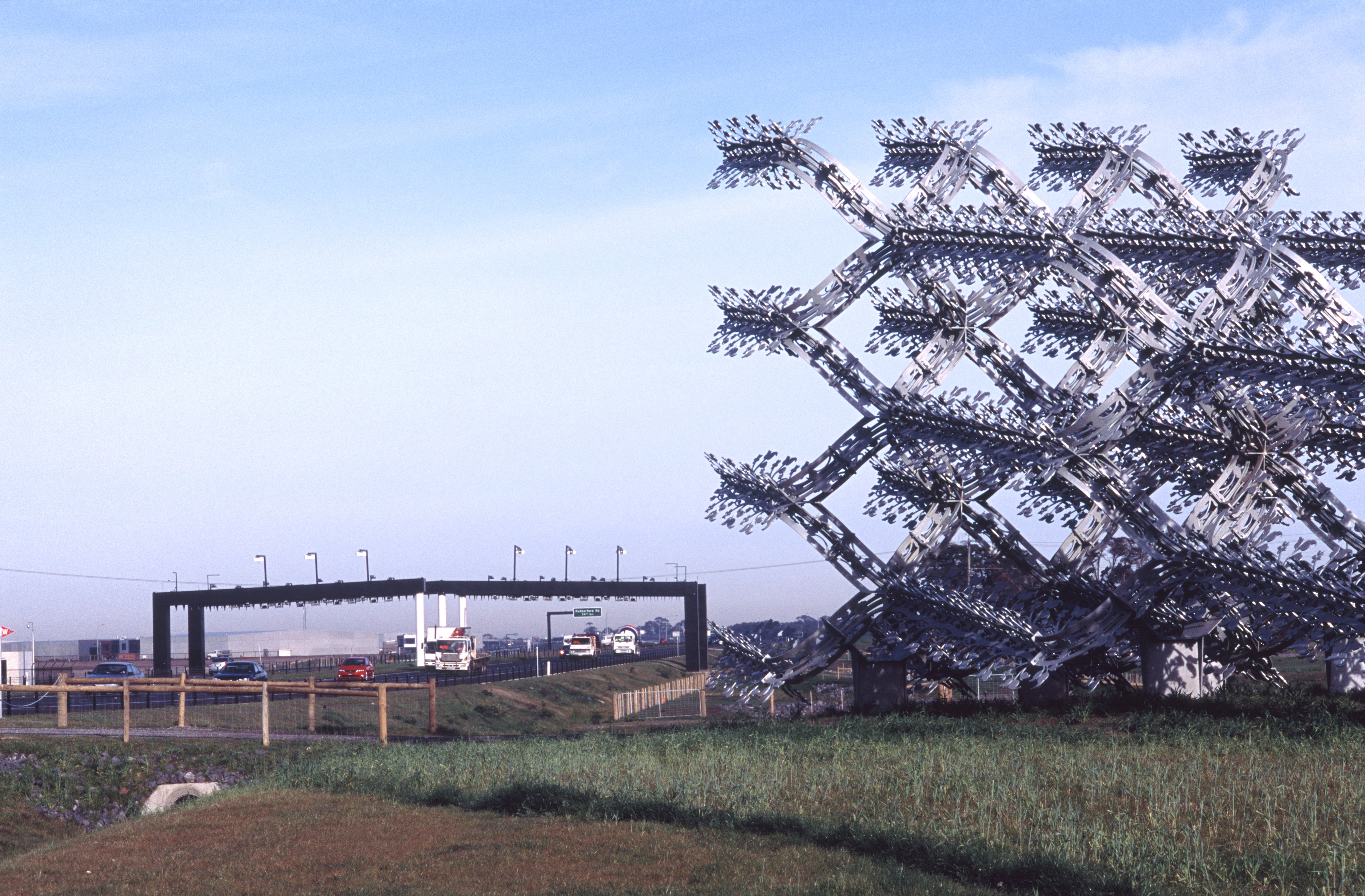

Cars, trucks and vans were taking to the new EastLink toll road in Melbourne with enthusiasm this July, pleased to try out its 39km route for time and cost savings. As well as the convenience of the uncongested route, drivers were also able to view an extraordinary multi-shaded perspective of transparent green and orange noise wall panels, burnt earth-coloured retaining walls and white and black bridges. This carefully designed road-scape is like no other in the world.Some of this initial delight may tail off because the road was toll-free for its first four weeks in use. Drivers will now have to pay a fee from just over A$1 for a short section to A$4.60 to travel the full road length. But the spontaneously expressed plaudits from taxi drivers, commuters and local delivery services suggest the link will retain its popularity.

Residents are already saying that it offers time savings of 30 minutes on what was previously a difficult and congested journey along one of two city highways, criss-crossed by junctions and with journeys broken by stops and traffic lights. Local industry has extended along the route in anticipation of its transport value and declares that this will cut hours from delivery times.

The EastLink will retain its time savings with tolling is underway, because it uses electronic free-flowing technology. Passing vehicles are registered by electronic tags which users can buy, or with high accuracy vehicle detection and number plate recognition to bill casual and occasional users.

Unlike most highways it has been carefully and deliberately designed with a full scale architectural input from the beginning, complemented by careful landscaping work. One of Melbourne's best known practices,

The Australian state of Melbourne has some of the world's highest standards for road noise attenuation, with no more than 63dBA allowed. This means all roads through the urban areas must have protection using embankments, noise panels and walling. Around 3,000 properties are close to the road so a large quantity of panelling has been used.

Wood Marsh made sure this panelling is in a variety of shapes and colours, with sculpted shapes and lines cast into the front. The panels form mixed patterns and shapes by being placed at different orientations. At the top of many of these walls are transparent panels of acryllic in light or dark green.

Around these panels and the embankments nearly 4 million new plants are growing, the outward sign of a major landscaping effort that complements the architecture and engineering structures.

Landscaping has also created park space and a nature reserve from some 60 different soakaway ponds, which the road construction created for its drainage needs, during the work and for the road. These are environmentally sustainable treatments for rain run-off from the tarmac with reed beds to filter the water and treat it, but they also help clean up degraded creek beds along the southern course of the road.

Environmental sensitivity is even more pronounced at the northern end of the road where a twin-bore tunnel carries its dual three lanes underneath an area of wild woodland. In the now sprawling city it is valued as one of the only pristine natural area left. Ironically the Mullum Mullum Valley (as this area is known) is a product of the desire for a road. City authorities reserved a corridor for a future highway in the 1960s and it could not be developed so that it gradually reverted to nature. Protests erupted when it was proposed to extend the Eastern Freeway so the Victoria state highways agency

These eastern areas have grown along with the Australian population. But despite the growing need, the highway also seemed to be beyond the government's purse as well. Federal contribution was not able to make up the difference.

Proposals were then made to fuse the two projects, which connect at the top anyway, and the EastLink was born with greater potential as a larger scheme.

Argument raged over how to fund it and eventually the government was persuaded to go the public- private partnership (PPP) route. It had done this for a previous road project in the city, the difficult, but eventually successful, City Link.

"It was the only way to get the project done," argued chief executive Ken Mathers of the South & Eastern Integrated Transport Authority (SEITA), a special dedicated body set up (from mainly VicRoads staff) to oversee pushing the project through once it was big enough to justify a special purpose body.

But a political promise by premier Steven Bracks had said "no tolls". When in 2002 the state government announced that after all it would be a paid-for road, there were political protests, although these have since faded away.

The intensive bidding process instigated by SEITA delivered the cheapest toll level in Australia. It also set up the competitive bidding process so as to draw out extra features for the road. During 12 months of bids and revisions in sharp competition, SEITA was able to get the two rival groupings to offer a variety of extras on the basic 39km road length.

There are two extra sections of road, 4.2km in all. These are east-west connections at Ringwood in the north and Dandenong halfway along the route, which create much-needed new bypasses for the settlements. There is a shared use pathway for the full length of the road, a 3m wide concrete paved route which will serve both cyclists and pedestrians in a country keen on both these outdoor pursuits. It connects into another 200km of bicycle network around the city. In places park furniture and timber walkways have been used to landscape the new wetland ponds and soakaways to create local community facilities.

In addition, the architect persuaded the concession company, which is running the road for the next 39 years, to add a number of artworks to the roadside. All these aspects have been picked up by a community relations team which has worked overtime to talk to the affected population along the route.

The same effort has been made by the design and construct contractor, which has kept itself well in touch with the local population during what is currently Australia's biggest construction project.

The company, the all Australian

In fact under its project director Gordon Ralph it managed to complete its work five months early, avoiding penalties for late delivery and instead, picking up bonuses on the A$2.5 billion project. It has been in everyone's interests naturally to complete the project as fast as possible: the concessionaire because it wants to start collecting tolls and the government (the client) because it wants to deliver a much-needed project.

The contractor on this occasion was working directly for the concession company, ConnectEast, in a conventional design and construct arrangement, even though TJH was part of the original bidding group along with merchant bank Quarry Bank. TJH owns a percentage of the concessionaire.

By having the Independent Reviewer in place, ConnectEast was able to look after its interests for the long term ensuring that road pavement quality and structures would meet the needs of the scheme, and would not be likely to impose excessive future maintenance requirements.

"And we share many of the interests of the government in that" says John Gardiner, the managing director of ConnectEast.