Mumbai is an important economic powerhouse for India; home to the country’s financial centre, the Bollywood film industry and capital of Maharashtra State. With an estimated 20.6 million inhabitants, greater Mumbai is India’s second most populous city after the capital Delhi, and is also the world’s eighth most populous city.

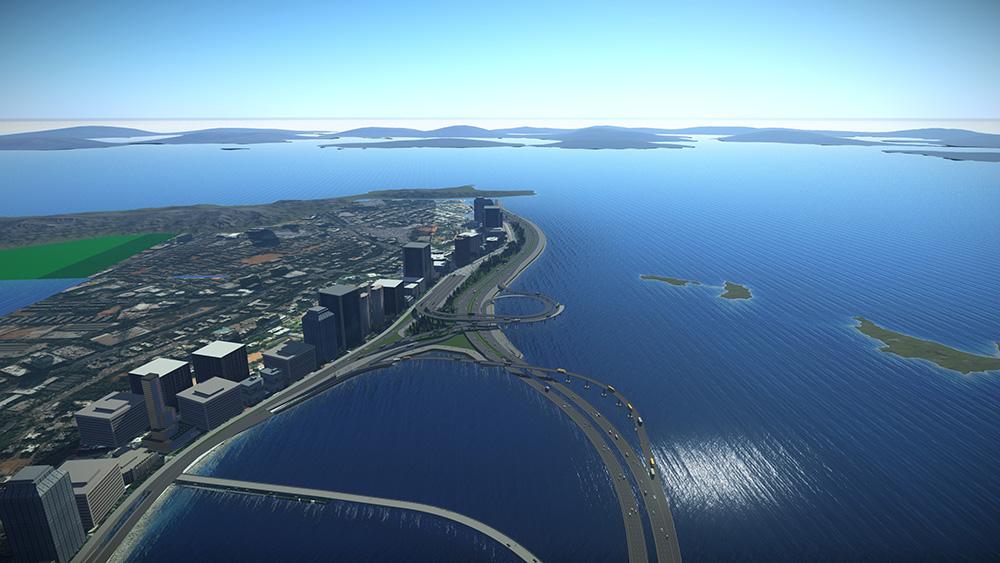

A mega city according to modern definitions, Mumbai is located on a peninsula on the southwest of Salsette Island. On the west is the Arabian Sea, while on the east is Thane Creek and to the north is Vasai Creek. Covering 4,355km2, greater Mumbai is constrained in terms of future growth due to its location on a peninsula and with a nature reserve in its northern end. Central Mumbai is even more cramped, home to an estimated 12.4 million people living in an area of just 437km2 and resulting in a high population density.

The city has suffered from its own commercial success, with its economic growth and population expansion having resulted in a massive increase in vehicle numbers. As a result, Mumbai’s traffic woes, which have been bad for decades, have worsened significantly over the last 20 years. According to a recent survey by TomTom, Mumbai is the world’s fourth most traffic-congested city. The survey says that fellow Indian city Bengaluru is the world’s worst city for traffic jams, with Philippines’ capital Manila in close second and Colombia’s capital Bogota in third.

The huge increase in congestion on Mumbai’s road network has had a negative effect for the city’s overstretched infrastructure. Drivers typically face long commute times and the numerous vehicles stuck in jams with their engines idling has made the already poor air quality even worse, with serious health implications as a result. For Mumbai’s inhabitants, this has made a bad situation even harder to bear.

Faced with the health hazard caused by exhaust pollution, the lost working hours and increased transport costs that could be traced directly to the traffic woes, a way ahead had to be found. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai carried out a series of studies for the island city and its surrounding suburbs in a bid to find a solution. The aim was to find a suitable method to reduce the frequent traffic jams, improve journey times and also address the traffic pollution issues.

However, it is of note that the idea of a new coastal highway for Mumbai is anything but new. In fact, the proposals for a new coastal road link for Mumbai actually date back 60 years. In 1962 Wilbur Smith and Associates suggested that a 3.6km coastal road link be constructed on reclaimed land connecting Haji Ali with Nariman Point, while a 1km tunnel stretch be bored under Malabar Hill to Girgaum Chowpatty. Although it was the topic of discussion for some discussion at the time, this project never left the drawing board and Mumbai’s traffic woes worsened all the while as its prosperity, human population and vehicle numbers grew. With India’s economic growth over the last 20 years, pressure on infrastructure in key cities has intensified and this has been highly apparent in Mumbai in particular.

In early 2012, a new report proposed the construction of a 35.6km coastal route to link Nariman Point to Kandivali, much of which would be built on reclaimed land. This proposal would have included raised portions, a number of bridges and a tunnel stretch, at an estimated cost of $1.3 billion.

One of the major barriers to this plan came from existing rules. India’s Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) legislation prevents land reclamation. As part of the alignment would run along reclaimed land, this meant that the CRZ would have to be relaxed to allow the project to go ahead.

The issue was discussed by the Maharashtra coastal zone management authority (MCZMA) in 2013, which came to the conclusion that an amendment of the CRZ legislation would be required by the Indian Government. This would allow land reclamation to be carried out for road building but not for other development works. In addition, the high tide level would not be affected, while the coastal road would also provide greater protection against flooding.

But there were complexities over various environmental concerns. As a result, the proposed amendments required to the legislation were sidelined and the progress with the CRZ stalled.

Mumbai’s traffic problems did not go away though and instead continued to worsen, forcing the authorities to take action. Eventually the necessary legislation changes were made that would allow reclamation works to be carried out for road projects. Once this had been achieved, the approvals for the works could be passed, allowing the go-ahead for the project to be given at last.

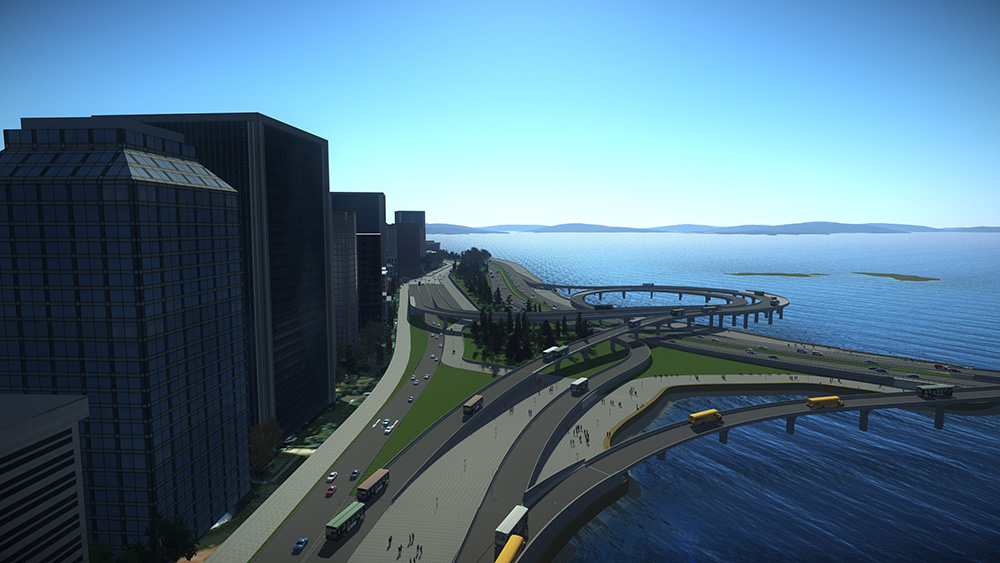

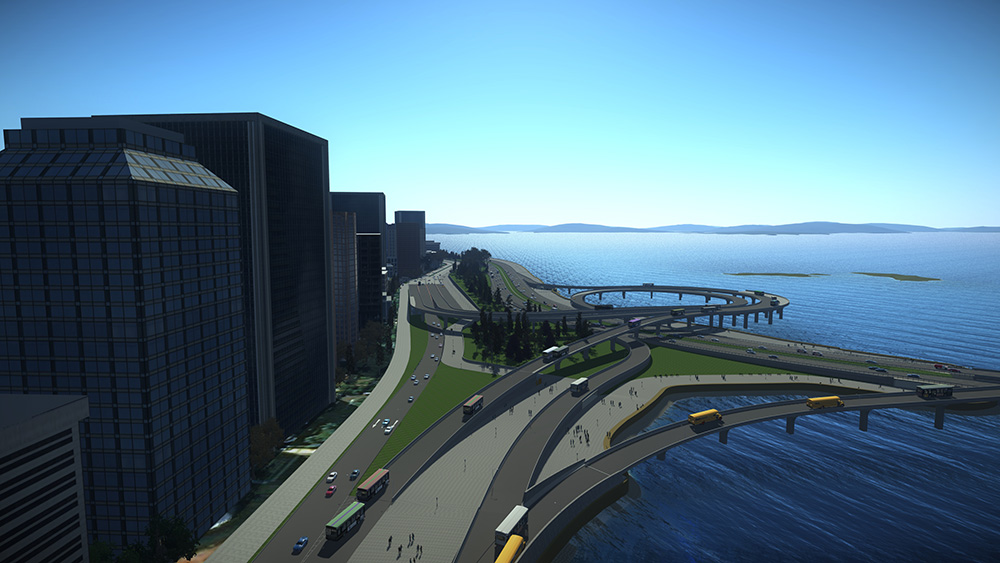

The SAI-SYSTRA Group (SYSTRA) won the contract to handle the work of design consultant for Package II of the project, the south end of the route. This is one of the most challenging portions of the project and the firm has been handling the design for a 2.7km stretch, worth around $306 million. The section is complex as it includes undersea tunnels, grade roads and bridges, and an interchange that connects the road to the Bandra-Worli Sea Link.

Another of the key issues the designers of the coastal road had to contend with was the risk of flooding, particularly for the tunnel section. The monsoon period between June and September frequently results in heavy flooding in and around the city. In 1954 a record rainfall of 3.45m was recorded and with the effects of climate change becoming apparent in many places around the world, Mumbai is highly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions.

An important portion of this work has been the addition of green spaces and waterfronts for recreational activities. But the space constraints along the coastal route required the reclamation of an area of 110ha.

SYSTRA employed software from Bentley Systems to design the horizontal and vertical alignment for the coastal road as well as an intersection near to the sea. Use of the Drive-through tools in the OpenRoads Designer software allowed clash detection processes to be carried out. This was carried out more speedily than would be feasible with conventional methods and, more importantly, helped to avoid issues with the sea wall or structure at a later stage in the development of the alignment for the project. With the availability of a comprehensive 3D model and its dynamic features, the team was able to refine the plan and reduce design time by around 50%. The use of the software was crucial as this provided the starting point for the project’s BIM architecture.

As much of the new coastal road was to be built on reclaimed land, this would have made calculating the quantities of materials required a particularly complex and lengthy task. But the use of the software meant that this stage of the process could be carried out accurately and in considerably less time than if using conventional methods.

Employing the OpenRoads Designer package meant that the design could also be optimised in a shorter timeframe, while maintaining quality. The use of the software helped to deal with a problem at one spot where the retaining sea wall would have obstructed the view of the sea from the promenade. By employing the 3D drive-through tool, SYSTRA was able to achieve a solution more easily and quickly.

Because the SYSTRA team was using software tools from Bentley Systems across a range of duties, interoperability between the various packages allowed the project team to communicate effectively and share changes.

Building the link

Back in 2018, a joint venture partnership was awarded the contract to build the Mumbai sea link crossing in India. The crossing was initially expected to cost US$1.05 billion to build with, the work intended to be carried out during a five-year building schedule. However, the prospect of the global pandemic brought delays to the project. Construction work was halted for a period at first but was then restarted once new working practices had been established that would provide the necessary protection for the workforce.

With an estimated cost of US$1.75 billion, construction is well underway on the 29km route. The project has been split into separate sections, with Package I for the construction of 10.38km-long bridge section across the Mumbai Bay and Sewri Interchange. Package II is for the construction of a 7.8km-long bridge section across the Mumbai Bay and Shivaji Nagar Interchange. Meanwhile, Package III is for the construction of a 3.61km-long viaduct, including interchanges at the State Highway (SH)-54 and at the National Highway (NH)-4B near Chilre in Navi Mumbai.

The work is being carried out in two main phases and is being overseen by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM). One of the most challenging technical aspects of the project is the construction of the tunnel section. An array of contractors, international as well as from India, are carrying out work on the various sections.

However, the project has faced other challenges also, and not only from delays caused by the current pandemic. In mid-2019, work was halted on legal grounds due to questions over the land required for the project and then recommenced in late-2019 following a new legal ruling. The legal case has continued in India’s courts, with the necessary environmental approvals having proven a major stumbling block. To address issues over land needed for the work, more land is being reclaimed, although this in itself has presented additional technical challenges.

Piling technology

Pile top drill rigs (PBA) by MHWirth have been used to provide solid foundations for India’s flagship project, the Mumbai Trans Harbour Link (MTHL).

Five Wirth PBAs 818 have been used at the MTHL project. MHWirth PBAs have been used to drill around 1,100 piles with diameters of 1.75m and 2.15m and to depths down to 50m.

The Largest Diameter TBM in India…

A large diameter tunnel boring machine (TBM) built in China has been used for the coastal road project in Mumbai, India. Manufacturer CRCHI built the TBM at its main facility in Changsha, China and the machine was shipped from Shanghai to Mumbai and used to help construct a tunnel stretch for the Mumbai Coastal Road Project.

Featuring an excavation diameter of 12.2m, this Slurry-type TBM measures 80m long and weighs 2,300tonnes. It has an installed capacity of 7,280kW and a gradeability of 5%. It was the largest diameter TBM ever used in India. The CRCHI Slurry TBM was used to drive a 1.92km tunnel comprising part of the route. The tunnel construction work had to deal with complex geological conditions that required excavation in deep overburden. The tunnel drive passed through strata including basalt, breccia and shale, featuring maximum uniaxial compressive strength up to 200MPa. To solve the challenges, the CRCHI Slurry TBM was constructed with a mixed cutter head featuring eight spokes and eight panels, which allowed the machine to bore through the complicated strata for the distance required. To solve problems such as mudcakes forming on the cutterhead and slurry discharge blocking, the TBM had to be fitted with a big-diameter slurry feeding port and several slurry flushing lines to increase the flow rate of slurry. In addition, 508mm-diameter disc cutters were fitted to the TBM to improve the machine’s rock breaking capacity and prolong its lifespan.

To further ease its operation, this CRCHI Slurry TBM was equipped with innovative features, such as a dual-chamber indirect slurry control system, a dual-circuit automatic pressure system, high-torque and retractable main drive, as well as a high-power slurry circulation system.