Indiana exercised its authority to use a P3 contract when it partnered with Kentucky for new bridges across the Ohio River. Barney Allison and John Smolen* explain the groundbreaking availability payment deal

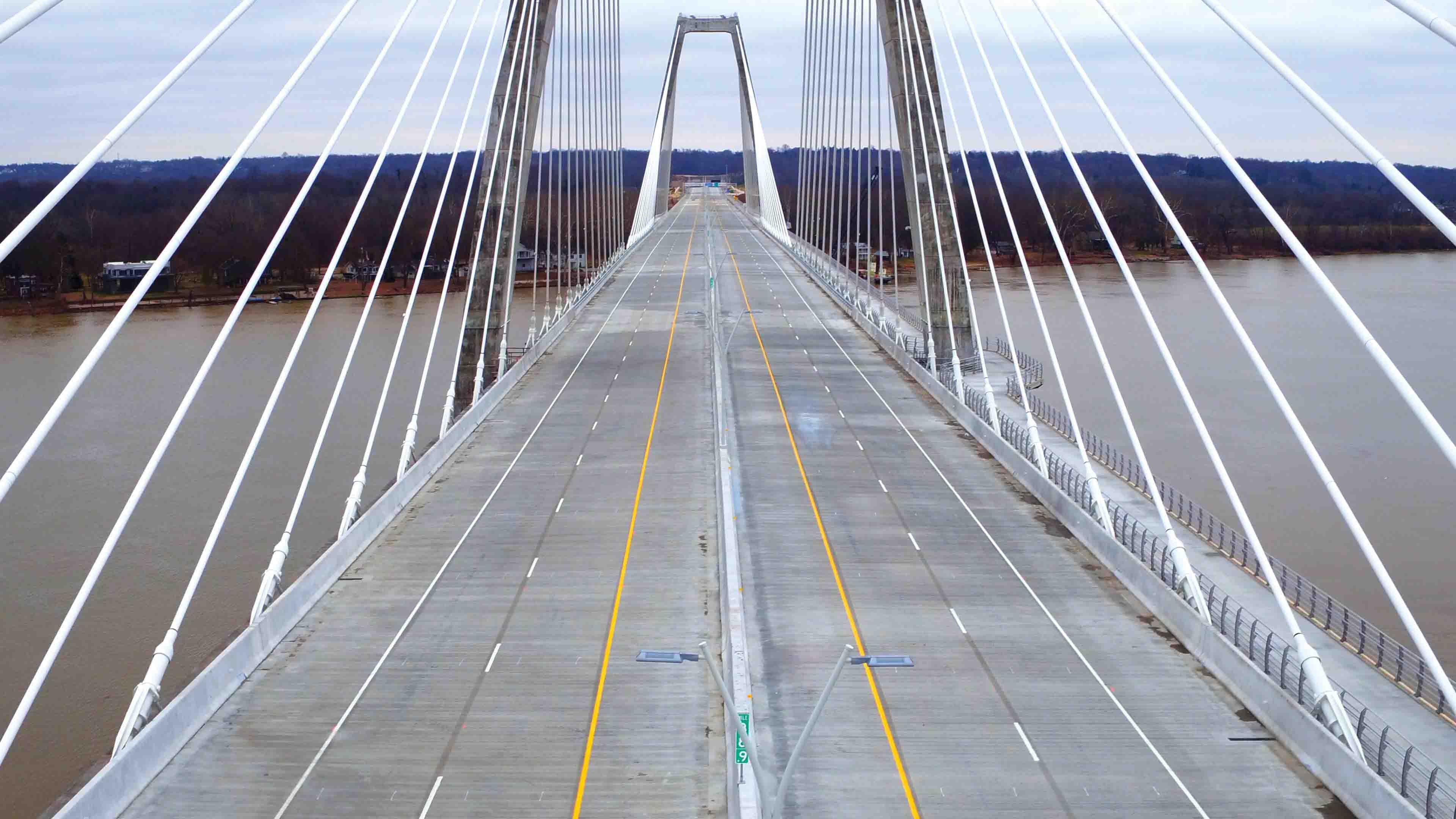

Earlier this year, traffic began rolling over the new tolled Lewis and Clark Bridge spanning the Ohio River from northern Kentucky to southern Indiana.

The cable-stayed bridge is part of the award-winning Ohio Bridges Project to untangle traffic within the greater metropolitan area of Louisville, Kentucky's largest city, located on the Ohio River along the Indiana border. In early March 2012, the governors of Kentucky and Indiana agreed to divide development of two new bridges that were to be the centrepieces of the Ohio River Bridges Project. They also agreed to divide significant approach work to the bridges, along with several multimodal improvements to increase transportation choices for area residents, including enhanced bus services as well as pedestrian walkways and bicycle trails.

The Ohio River Bridges Project called for tolling the existing John F. Kennedy Bridge and a new Abraham Lincoln Bridge – the Downtown Crossing project of the overall Ohio River Bridges Project. Kentucky was responsible for the Downtown Crossing project. Meanwhile, Indiana was responsible for the East End Crossing consisting of a new East End Bridge - later renamed the Lewis and Clark Bridge.

Toll revenue would be shared 50/50 between Indiana and Kentucky. But Kentucky and Indiana were to follow very different procurement routes for their individual responsibilities within the overall Ohio River Bridges Project.

Different paths

Indiana’s Department of Transportation chose a public-private partnership (P3), known internationally as an availability payment (AP) structure for its East End Crossing. Meanwhile, the companion Downtown Crossing project was delivered by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet using a more traditional public financing approach.

Kentucky elected for a design-build procurement for the Downtown Crossing, a six-lane cable-stayed Abraham Lincoln Bridge parallel to the existing downstream Kennedy Bridge. The Abraham Lincoln Bridge carries northbound traffic on I-65 across the Ohio River while the six-lane John F. Kennedy Bridge now handles southbound traffic.

Kentucky’s work included reconfiguration of the so-called Spaghetti Junction of Interstates I-64, I-65 and I-71 in downtown Louisville. The Transportation Cabinet raised money by issuing debt secured by Kentucky’s share of tolls from both bridge works.

Indiana governor Daniels, through the Indiana Finance Authority (IFA), in conjunction with the state department of transportation used an AP P3 for the East End Crossing. Work covered almost 13km of road east of downtown Louisville. A 761m-long East End Bridge was to span the river in eastern metropolitan Louisville, connecting I-265/Gene Snyder Freeway in Kentucky with the Lee Hamilton Highway in Indiana, including approach roadways in both states.

Indiana was also responsible for approach road work which included 6.6km of highway construction and in Kentucky an approach road that featured 5.3km of highway construction, including around 609m of twin-bore tunnel, two lanes each, beneath the historic Drumanard Estate, a 1920s-era property on the National Register of Historic Places.

Due to the bi-state nature of the Ohio River Bridges Projects, it was essential for IFA and the states’ transportation agencies to work closely. They broke new ground in that each state constructed improvements in the other’s territory. Importantly, each state provided a comparison of design-build versus P3 delivery.

While Kentucky sought the efficiencies of design-build, at the time the state did not have statutory authority to enter into P3 transactions. Indiana, however, did and selected the design-build-finance-operate-maintain (DBFOM) P3 option for its East End Crossing. This included a 35-year term for operation and maintenance of Indiana’s portion of the overall Ohio River Bridges Project. In short, the winning consortium of contractors and bridge operator would take into account the long-term life cycle cost risks of what they were to design and build.

The Indiana Finance Authority and

• Led by

• Walsh Investors is the investment division of the family business Walsh Group, one of North America’s largest general contracting, construction management and design-build firms

•

• Bridge design consultant was International Bridge Technologies

• Steel fabricator was High Steel Structures (6,051 tonnes)

• All-electronic, no-stop tolling is used on the entire Ohio River Bridges Project that includes a new downtown Louisville interchange

Calibrating risk

Early P3s in the US adopted a strict model by which a private sector concessionaire would develop, deliver, operate and maintain an infrastructure asset that generated user fees. For toll roads, the concessionaire was granted the right to collect and occasionally set tolls which financed the transaction.

At the end of a term, the public agency granting the concession received the toll road back. Based upon user - or traffic volume - projections, the confidence that team members within a concessionaire consortium had in one another (and the prospects of controlling the attractiveness of the asset they deliver) meant that toll concessions began to carry some momentum.

The state of Texas led the country in solving infrastructure challenged by toll concessions (see following article). Indeed, Indiana tried its hand with a longer-term toll concession of the Indiana Toll Road.

But then the “Great Recession” happened in the US and the private sector’s appetite to take revenue risk cooled. A second type of P3 – the Availability Payment (AP) model of P3 – grew more attractive. Public agencies and sponsors explored how to deliver higher nominal cost projects under P3 structures to harness as much of the innovation and investment of private sector partners as was available, along with the transfer of long-term life cycle cost risk.

In AP transactions, the public agency retains the revenue risk and keeps project revenues, if any. Instead of utilising user fees to service its financing, the concessionaire counts upon programmed construction - or milestone -

payments and periodic, usually monthly, availability payments. Availability payments are for ensuring the infrastructure facility is available for use and meets agreed performance measures.

The AP P3 also opened up the advantages of P3 project delivery to infrastructure projects that don’t lend themselves to user fees, such as municipal hospitals, courthouses and other public buildings.

But availability payment structures are not without risk to the concessionaire. The concessionaire is evaluated on objective performance criteria; if the asset doesn’t perform as specified, availability payments are reduced. If the asset isn’t delivered on time, milestone payments and commencement of availability payments are delayed.

Finally, at the end of the concession term, usually 30-35 years, the asset must meet an agreed-upon remaining useful life condition, referred to as handback condition.

The state of California pioneered the availability payment model in January 2010, closing on the $1.1 billion Presidio Parkway project under a lease structure. Florida also put together hybrid toll concession/availability payment P3s under concession contract structures in its $1 billion Port of Miami Tunnel and $2.3 billion I-4 Ultimate projects (see

Indiana’s East End Crossing project was to be the next - and slightly bigger at $2.6 billion. But this time it included a bridge, as well as a tunnel. It also was to be the first pure AP transportation concession P3 in the US.

Both Indiana and Kentucky, still in the wake of the Great Recession, favoured quicker delivery to start the revenue stream from user fees on the tolls. But Indiana had the P3 structure available to it and the AP structure with that. Those objectives and the project characteristics – a tollable facility – lent the East End Crossing to a P3 contract type. Indiana would use that structure to achieve those objectives.

But Indiana faced a challenge. It had to proceed with procurement while coordinating with Kentucky for technical reviews and operating standards. Indiana also had to start right-of-way acquisition of property across the border in Kentucky. This required a keen sense of teamwork and an alignment of interests between parties in both states.

Timing was everything

The Bridges

ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIDGE (NEW) – DOWNTOWN CROSSING

• Opened December 2015

• Cable-stayed, 640m long, three sets of

twin towers

• Six lanes northbound of I-65

JOHN F. KENNEDY MEMORIAL BRIDGE (RENOVATED) – DOWNTOWN CROSSING

• Opened 1963 and renovated 2016

• Cantilever, 761m long

• Six lanes southbound of I-65

LEWIS AND CLARK BRIDGE (NEW) - EAST END CROSSING (INITIALLY THE EAST END BRIDGE)

• Opened December 2016

• Cable-stayed, 761m long

• 35,000 vehicles daily expected big advantage of full DBFOM P3 projects is that they allow for the private sector to offer innovative concepts in design, delivery and financing. It was also essential that participants in the East End Crossing set a schedule and stuck to it. And some good fortune was to be welcome considering there were to be separate procurements. It ultimately involved all-party commitment to the project, largely at the exclusion of other projects.

In early March 2012, IFA, with INDOT, held an industry forum to roll out its conceptual plans for the East End Crossing. Later that month, IFA issued a Request for Qualifications (RFQ), soliciting statements of qualifications from prospective proposers to develop, design, build, finance, operate and maintain the East End Crossing through an AP concession. After receiving six statements of qualifications in early April, IFA shortlisted four teams on April 23. Following an active “industry review” process, heavily informing the final Request for Proposals (RFP), IFA issued its RFP on July 31.

Proposals submitted by the late October deadline were evaluated quickly but thoroughly and on November 16, 2012, a selection was made: the WVB East End Partners joint venture (see box). Planned substantial completion of the project was bid by the end of October 2016 – almost nine months before the date specified by IFA and INDOT.

The East End Crossing concession win was a first for both Walsh and VINCI to be in an equity role in the US P3 market. Coincidentally,

As part of the procurement processes, Indiana and Kentucky had worked out a bi-state development agreement that ensured neither state stood in the way of the other in keeping its development on schedule. Topics ranged from how to handle changes to the scope of work that affected portions of each project that rested within their respective jurisdictions - ledger-sheet tracking of payments - and how to share tolls and toll operations.

But most importantly, both states believed wholeheartedly that good communications were imperative to successful overall procurement.

As a result of this bi-state alignment of interests, the East End Crossing, at the time of its commercial closing, was the fastest P3 procurement for its scale in the US. It went from RFQ to commercial close in just under eight months. Its financing was the fastest to financial close, at 12 months.

More spectacularly, IFA, its partners, each of the six proposers, four shortlisted proposers and the eventual concessionaire/developer kept each committed deadline set during procurement.

Creative Financing

A second, and significant objective of IFA was to maximise the opportunity for innovative financing. Toll revenue hadn’t yet started to flow. Nonetheless, Indiana made the considered judgment not to risk progress on the project by applying for federal funding under the so-called Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) programme. Instead, based upon a desire for rapid, but considered delivery, Indiana sought innovative financing from its proposers and the WVB consortium delivered on the opportunity.

The WVB consortium proposed a construction price of $764 million (23% below engineering estimate) and maximum availability payments for the term of $32.9 million (in 2012 dollars) per year. The parties closed on the Public Private Agreement (PPA) on December 27, 2012.

The WVB consortium planned to raise nearly $1 billion of public and private debt and equity funding. IFA, as both public sponsor and counterparty to the PPA, was to serve as conduit issuer for the private activity bonds (PABs). The East End Crossing became the first US transportation P3 transaction not to take advantage of TIFIA!

To finance the project, the WVB consortium had to rely on its equity investment and a bond solution. Equity members contributed around $78 million towards project costs. The balance of the financing consisted in bond debt: two series of tax exempt private activity bonds (PABs). Series A, in the principal amount of $482,310,000, with maturities starting in July 2035 and final maturity in January 2051; and pricing for these “long bonds” between 4.56% and 4.96%.

WVB proposed a third tranche for construction financing in the principal amount of $194,495,000, with nominal maturity of January 2019, structured for earlier calls as construction period “milestone payments” were achieved and priced to yield 2.28%. As it happened, the financing of the East End Crossing was then the largest PAB issuance in the country’s P3 history.

In the time between commercial close and financing, the risk allocation regarding credit spreads posed a potential price challenge – the cost of a quick transaction – amplified by the fact that WVB’s financing plan was largely the bond solution. Attractive pricing for the bonds, however, helped reduce the risk of changes in long-term municipal bond rates from proposal submission, which in turn resulted in very little change in the availability payment at the financing. A little more of that good fortune had arrived. The East End Crossing project was the first US availability payment P3 project to achieve “flat” investment grade ratings from S&P and Fitch.

Looking forward

The project was substantially completed in late December last year and finally accepted in April 2017, a nominal delay of only six weeks over a nearly four-year design-build period. The Downtown and East End Crossings came in roughly at the same time. The risk sharing approach within the East End Crossing PPA during the design and construction phase resulted in an increase of only under 2% in the total design-build price, a remarkable achievement for a project of this size and complexity.

Looking to the future, Kentucky’s taxpayers must trust in the good governance of the state budget process to ensure that enough cash will be available to operate and maintain the Abraham Lincoln Bridge.

In Indiana, however, the WVB consortium remains as concessionaire under contract to IFA; operation and maintenance of the Lewis and Clark Bridge rests with WVB. For a cable-stayed bridge that spans a river prone to winter freezing and spring flooding, this is a significant allocation of risk to the private sector.

Overview: Ohio River Bridges Project

CLIENT: Indiana Finance Authority, in concert with the Indiana Department of Transportation

PROJECT COST: $2.6 billion concession cost of which around $1.1 billion for the East End Crossing/Lewis and Clark Bridge

KEY CHALLENGES: Multi-jurisdiction project; Beta testing of availability payment P3 with objectives of innovative financing and early delivery

The opening of the 762m cable-stayed Lewis and Clark Bridge in December marked the end of the ambitious project. It was conceived in 1998 and took three-and-a-half years to construct - the largest road and bridge development jointly undertaken by the neighbouring US states of Indiana and Kentucky. It was also one of the largest transportation improvements in the country and designated by the US Congress as one of 13 projects of national importance

It consists of two bridge sub-projects – Kentucky’s $1.3 billion Downtown Crossing (new Abraham Lincoln Bridge) and Indiana’s $1.1 billion East End Crossing (new Lewis and Clark Bridge)

Downtown Crossing/Abraham Lincoln Bridge - Lead contractor Walsh

East End Crossing/Lewis and Clark Bridge – Work consisted of nearly 14km of new road, including two parallel 518m tunnels and the new 762m cable-stayed Lewis and Clark Bridge. The new Lewis and Clark Bridge and road, opened in December 2016, connect the eastern edge of suburban Louisville in Kentucky and an area just east of Jeffersonville city in Indiana.