Patrizia Bellucci from the Research and New Technologies Division of ANAS, in Rome introduces a sustainable approach to road noise abatement Traffic noise has been recognised by the World Health Organization as a major factor contributing to environmental pollution. Besides causing annoyance, it has significant negative health impacts on populations living close to road infrastructure. In 2002, to help counter this state of affairs, the European Parliament and Council adopted Directive 2002/49/EC relating t

A zig-zag photovoltaic noise barrier has been installed in the Vallese di Oppeano in Italy as the first test stretch

Patrizia Bellucci from the Research and New Technologies Division of

The main aim of the Directive was to define a common approach aimed at avoiding, preventing or reducing the harmful effects of noise. To this end, Member States were required to determine levels of exposure to environmental noise through common strategic noise mapping procedures and to adopt action plans aimed at reducing their impacts.

By 2008, at the conclusion of the first round of END, several Member States were voicing complaints regarding the lack of financial resources available for noise abatement measures. This problem is expected to have intensified by the time the results of the second round of noise mapping are made available in 2013. If they are to be successfully implemented, noise mitigation measures require consistent funding, and their economic and financial impacts cannot be sustained by road administrations within a reasonable timeframe without the benefit of Government support.

Such funding dilemmas are typically faced by Governments seeking to levy the necessary resources by stepping up taxation in various areas (fuel, road tolls, urban access, vehicle licensing, and so on) that are already subject to negative social and economic impacts. It is therefore helpful to investigate alternative financial models to help overcome the heavy additional economic burden resulting from the obligation to equip road networks with noise mitigation measures.

One promising approach might be to exploit the potential of integrating photovoltaic modules in noise barriers. Photovoltaic noise barriers (PVNB), as they are commonly referred to, enable effective noise abatement to be combined with the simultaneous production of renewable energy.

Besides helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, adoption of PVNB carries a range of other positive economic, social and environmental benefits. One of the most tangible is clearly the financial income that can be derived from the sale of the electricity produced. Depending on the prevailing price, and any subsidies available to promote renewable energy, this can help reduce the Life Cycle Cost (LCC) of noise reduction devices by up to 30% - a conclusion backed up by a number of current case studies. The figure could be even further improved through the development of specific financial tools aimed at providing incentives.

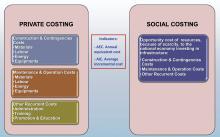

The remunerative nature of PVNB could make the technology an ideal vehicle for accessing both private and public financial resources and optimising their respective allocation. Indeed, the potential for sharing the costs of the infrastructure involved (such as PV plants and noise barriers), could enable a maximum of public expenditure to be directly dedicated to noise abatement activities.

In this way, the financial burdens of compliance, with not only Member State obligations under END but also the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, could be lowered, thereby significantly reducing the economic pressure on public administrations. Parallel benefits may also be anticipated in the renewable energy sector due to the creation of a new market niche for stimulating the circulation of private investment capital and supporting economic growth.

Other noteworthy environmental and social impacts include decisive reductions in the health and social costs caused by noise pollution, a faster response to noise abatement requests and the implementation of more extensive mitigation measures thanks to the availability of wider investment capital from the private sector.

Notwithstanding the important environmental benefits that can be expected to flow from the widespread installation of photovoltaic plants, however, the imperatives of the current financial crisis have tended to divert Government strategies towards drastic reductions in the public subsidies previously available for the renewable energy sector. Such cuts in public incentives have also been motivated by a steady growth in energy prices and by the imminent projected attainment of the so-called ‘grid parity’ (balance of costs and revenues) that would render photovoltaic systems virtually self-sustaining. Given this trend, new forms of incentives and financial support will be required to exploit fully the beneficial effects of integrating photovoltaics in noise barriers.

If solid Government support is forthcoming, PVNB have tremendous potential for becoming economically self-sustaining. To support implementation, specially tailored public/private financial protocols should be explored in order to encourage private investors to feed the new market opportunity. Similarly, evidence of the benefits expected from the introduction of PVNB should be carefully assessed and packaged so as to demonstrate a viable and attractive business case for financiers. In particular, the veracity of assumptions - such as the possibility of making PVNB self-sustaining through special energy sale conditions and/or public incentives to energy producers investing in the new application; or the opportunity of reducing costs by implementing integrated photovoltaic panels with advanced technological solutions - should be rigorously validated. The availability of such information would provide Governments with coherent and credible tools through which to evaluate the prospects for supporting the application.

A comprehensive evaluation of the technical, legislative, environmental and financial aspects that affect the implementation of photovoltaic noise barriers should be promoted at EU level in order authoritatively to demonstrate PVNB capability in terms of reducing the financial implications of effective noise mitigation measures whilst, at the same time, boosting the creation of a new niche in the renewable energy market.